A political shockwave is rippling through the defense and diplomatic communities as Canada’s government delivers a stunning public critique of its long-planned F-35 fighter jet procurement, openly courting a rival Swedish offer that promises a transformative domestic industrial boom.

Industry Minister Mélanie Joly has declared Canada’s returns from the multi-billion dollar F-35 program insufficient, directly challenging the cornerstone of allied airpower strategy. Her statement signals a potential historic pivot, placing economic sovereignty and alliance loyalty on a direct collision course.

“I don’t believe that we’ve had enough jobs created and industrial benefits done out of the F-35 contract,” Joly stated during a parliamentary hearing. “Canadians expect more and we should get more.” This unprecedented public dissatisfaction from a key minister has ignited a fierce debate over Canada’s defense future.

The catalyst for this crisis is a bold, unsolicited offer from Sweden’s Saab. The company proposes establishing a complete Gripen E fighter production line on Canadian soil, a move it claims would generate 10,000 high-tech jobs and create a sovereign aerospace manufacturing hub. This offer fundamentally reframes the fighter replacement program. It is no longer merely a military procurement but a choice between deepening integration into a U.S.-led defense ecosystem or pursuing a path of greater industrial independence and domestic capability building.

Canada has been a founding partner in the F-35 program for over two decades, investing hundreds of millions into its development. The expectation was guaranteed access to the global supply chain for the thousands of aircraft planned worldwide.

Analysts note a persistent imbalance, however. Canadian work has largely been in subcontracting roles, failing to build the core research or manufacturing independence that would secure long-term technological benefits. The financial burden remains in Ottawa while advanced technological gains concentrate in the United States. Saab’s Gripen proposal directly targets this frustration. It promises not just assembly, but full technology transfer, training for Canadian engineers, and a domestic supplier network capable of supporting the entire aircraft throughout its lifecycle.

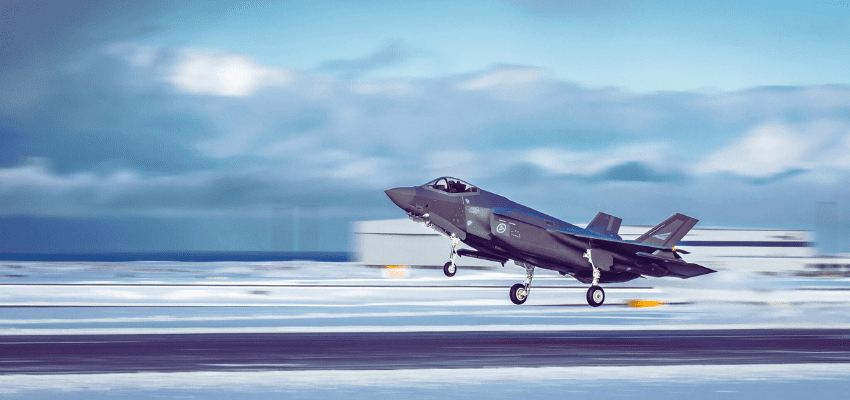

The Swedish manufacturer also emphasizes operational advantages for Canada’s unique environment. Developed for Scandinavia’s harsh climate, the Gripen is engineered for operations from snow-covered runways and in extreme sub-zero temperatures, a critical requirement for Arctic defense.

Economic arguments are potent. Estimates suggest the Gripen’s cost per flight hour is a fraction of the F-35’s, potentially allowing for more pilot training and higher mission readiness without straining maintenance budgets.

The F-35’s advocates underscore its unmatched fifth-generation capabilities, including stealth and deep network integration within NATO and NORAD. Its selection would ensure seamless interoperability with the United States, Canada’s foremost defense partner.

This interoperability, however, comes with constraints. The F-35 operates as a closed ecosystem, with software, upgrades, and sensitive repairs tightly controlled by the U.S. government and Lockheed Martin, limiting Canada’s ability to modify or independently sustain the fleet.

The Gripen, by contrast, uses an open architecture philosophy. This has allowed operators like Brazil to integrate domestically developed weapons and systems without seeking foreign permission, a model of sovereignty Canada is now actively considering. The political stakes are immense. Washington views the F-35 as the ultimate instrument of alliance binding, creating long-term strategic dependency. A Canadian departure would send a destabilizing signal to other allies about the viability of alternatives.

Reports indicate American officials have expressed deep concern. They argue that a different fighter fleet would complicate joint operations, data sharing, and coordinated defense of North American airspace through NORAD.

Ottawa’s deliberations appear part of a broader strategic shift under Prime Minister Mark Carney. His government is actively diversifying defense and economic partnerships, moving beyond a reliance on any single axis of power. A recently signed security pact with South Korea, a rising defense manufacturing powerhouse, exemplifies this strategy. It aims to foster cooperation in technology transfer and critical minerals, building a more resilient, multi-polar network.

Carney’s vision, informed by his central banking background, explicitly aims to transform Canada from a supplier of raw materials into a manufacturer of finished, high-value goods like aircraft and warships, retaining skilled jobs and economic value at home.

The question now is whether operational necessity or industrial ambition will prevail. Can a single-engine Gripen truly meet the vast geographic demands of Canadian patr ols from the Arctic to the Atlantic and Pacific coasts? Critics also ask if this pursuit of sovereignty simply trades technological dependence on the United States for a new reliance on Swedish aerospace expertise and intellectual property, rather than achieving true independence.

Defense planners are at a profound crossroads. The decision will resonate for decades, defining Canada’s role in allied defense structures, the strength of its aerospace sector, and its capacity for strategic autonomy in an increasingly volatile world. Minister Joly’s hammer-blow critique has thrown the previously settled F-35 plan into unprecedented doubt. With a concrete, jobs-rich alternative on the table, Ottawa faces a defining choice that will reshape its military, its industry, and its alliances.

The coming months will reveal how far Canada is willing to go in recalibrating the balance between alliance loyalty and national industrial ambition. The pressure from both domestic economic promises and international diplomatic expectations is now intense and unavoidable.