In a striking break from decades of U.S.-Canada trade tradition, Prime Minister Mark Carney has flatly rejected American demands on dairy access, digital policy, and alcohol sales—sending a clear signal that Ottawa is no longer negotiating from fear. The response, calm but unequivocal, marks a turning point in bilateral relations. As Washington presses for concessions it once assumed were inevitable, Canada is reframing itself not as a dependent junior partner, but as a strategic power with leverage, options, and alternatives. The shift could redefine North American trade for years to come.

For decades, U.S.-Canada trade negotiations followed a familiar script. Washington applied pressure, Ottawa absorbed it, and compromises were framed as the cost of maintaining privileged access to the world’s largest consumer market. Beneath it all sat a largely unchallenged assumption: Canada needed the United States more than the United States needed Canada.

That assumption is now being openly tested.

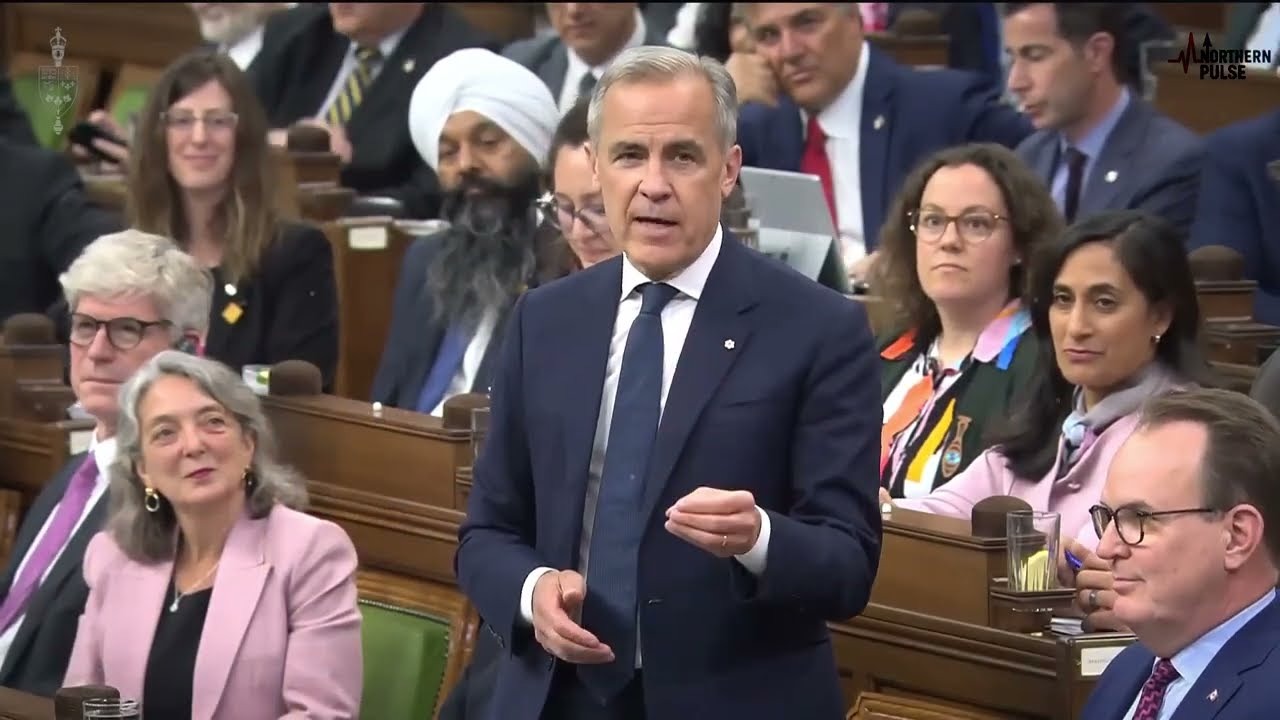

In recent trade discussions, Canada has rejected U.S. demands for expanded access to its dairy market, changes to digital taxation rules, and the rollback of provincial alcohol restrictions. When U.S. Trade Representative Jameson Greer presented these requests to Congress, the tone suggested confidence—perhaps even expectation—that Canada would eventually yield. Instead, Prime Minister Mark Carney delivered a brief but decisive response: supply management was “not negotiable.”

It was not defiant. It was not theatrical. And that, precisely, is what made it consequential.

Carney’s posture signals a deeper shift in Canada’s diplomatic strategy. Rather than framing negotiations around what Canada must concede to preserve access, Ottawa is increasingly focused on what the United States depends on—and what Canada is prepared to protect. The refusal to negotiate dairy access was not an isolated decision; it was a declaration that certain pillars of Canada’s economic model are no longer bargaining chips.

The U.S. demands themselves, while framed as routine trade “corrections,” reveal an uncomfortable reality for Washington. Access to Canadian dairy, relief from digital taxes, and expanded alcohol sales are not trivial asks. They speak to U.S. industries facing competitive pressure at home—and to a growing reliance on Canadian markets, energy, and materials to maintain economic stability.

Carney used this moment to reframe the conversation. Rather than debating individual concessions, he emphasized the deeply integrated nature of North American supply chains—particularly in auto manufacturing, steel, and aluminum. These are not symbolic partnerships. They are operational dependencies that underpin daily economic activity across the United States.

One example stood out: aluminum. Canada produces aluminum with significantly lower energy intensity than U.S. producers, saving enormous amounts of electricity while helping American manufacturers meet climate and cost targets. This is not a theoretical advantage. It is a structural one. And it underscores a central point Carney has begun to articulate more openly: Canada is not merely a market—it is an enabler of U.S. economic competitiveness.

That reality complicates Washington’s traditional leverage.

At the same time, Canada is actively challenging the long-held belief that it has no meaningful alternative to the U.S. market. With two coastlines, expanding trade agreements, and increasing engagement across Europe and the Indo-Pacific, Ottawa is positioning diversification not as retaliation, but as resilience. The message is subtle but unmistakable: access to the U.S. is valuable—but no longer existential.

This recalibration is not happening in isolation. Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s approval of a Ronald Reagan-themed advertisement aimed directly at American audiences illustrates how coordinated Canada’s approach has become. The ad reframes Canada not as a trade adversary, but as a trusted partner—appealing to U.S. political memory while quietly reinforcing Canada’s strategic value.

Together, Carney and Ford represent a new dual-track strategy: economic precision paired with political instinct. It disrupts the old narrative in which Canada absorbs pressure behind closed doors while projecting compliance in public. Instead, Ottawa is now openly evaluating the terms of its relationship with Washington—and signaling that those terms are no longer automatic.

The implications are significant. If Canada is no longer willing to concede on core economic policies without tangible returns, future negotiations will look fundamentally different. Access to Canadian markets, resources, and cooperation will increasingly be conditional—earned through mutual benefit rather than assumed through proximity.

This moment marks a departure from quiet accommodation toward deliberate assertion. It does not signal hostility, but it does suggest a reset. Canada is not walking away from the United States. It is renegotiating the premise of the partnership itself.

The era in which Washington could rely on Canadian capitulation appears to be ending. In its place is a more balanced, more calculated framework—one that treats trade not as a hierarchy, but as a transaction between equals. Whether the United States adapts to that reality may determine the next chapter of North American economic relations.