A single train rolling into Mexico City this fall may mark a turning point in North American trade. For the first time, Canadian grain traveled more than 3,200 miles from the Prairies to Mexico without touching a U.S. port or export terminal—bypassing infrastructure long considered indispensable. Backed by Prime Minister Mark Carney and powered by a newly integrated continental rail network, the shipment signals a deeper shift underway: Canada is redesigning its trade routes, reducing dependence on U.S. chokepoints, and reshaping the balance of power in agricultural markets. What looks like logistics is, in fact, geopolitics by rail.

The train that arrived in Mexico City in September did more than deliver wheat. It delivered a message.

Departing from Manitoba and traveling uninterrupted to the heart of Mexico, the shipment marked the first time Canadian grain reached Mexican buyers without relying on U.S. export terminals, ports, or handling facilities. For decades, those American nodes acted as unavoidable gateways for North American agricultural trade. That era, quietly but decisively, may be ending.

Prime Minister Mark Carney’s appearance at the arrival ceremony underscored the political weight of the moment. This was not a ribbon-cutting exercise. It was a signal—to farmers, to trading partners, and to Washington—that Canada is no longer structuring its economy around U.S. infrastructure assumptions that once felt permanent.

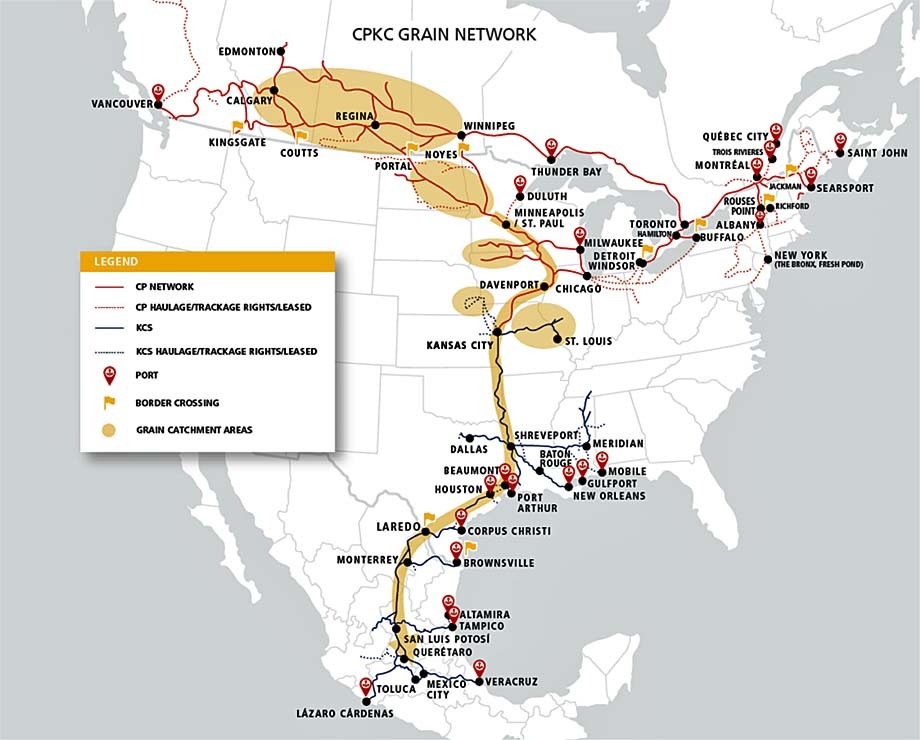

At the center of this transformation is Canadian Pacific Kansas City (CPKC), the first railway to directly link Canada, the United States, and Mexico under a single operating system. The acquisition of Kansas City Southern created a seamless north–south corridor, eliminating handoffs, delays, and bottlenecks that had traditionally favored U.S. terminals.

What that means in practice is simple but profound: Canadian grain can now move directly from prairie elevators to Mexican mills with fewer intermediaries, lower costs, and greater predictability. In an industry where margins are thin and reliability is everything, this is not a marginal improvement—it is a structural advantage.

For U.S. exporters and terminal operators, the implications are sobering. American ports that once captured value through blending, storage, and handling are seeing volumes decline. Grain that used to stop, wait, and generate revenue now simply passes through—or bypasses the country altogether.

The shift did not happen overnight, nor is it purely political. Canadian exporters have spent years responding to growing volatility in U.S. trade policy, from tariff threats to regulatory uncertainty. Mexico, by contrast, has emerged as a stable, contract-driven partner, eager for dependable supply and less entangled in domestic political turbulence.

As a result, Canadian ports such as Vancouver and Prince Rupert are handling record grain volumes, absorbing business that once flowed south before heading overseas. Meanwhile, American export terminals are facing a future where their leverage is no longer guaranteed by geography alone.

This new reality is reinforced by infrastructure investment. Canadian railways have expanded high-capacity hopper fleets, upgraded scheduling systems, and optimized routes not for continental convenience, but for national control. The introduction of electronic phytosanitary certification for shipments to Mexico has further streamlined the process, reducing delays and eliminating paperwork friction that once favored established U.S. systems.

For U.S. exporters, the loss extends beyond volume. Blended logistics and shared handling once allowed American firms to spread costs and maintain competitive pricing. As Canadian shipments increasingly run independently, those efficiencies erode. Higher per-unit costs and lower throughput threaten to weaken U.S. competitiveness over time.

Perhaps most consequential is the shift in habits. Trade is not governed only by price, but by trust and routine. Once buyers adjust to new routes that perform reliably, reverting becomes unlikely—even if political conditions change. Contracts are signed, relationships deepen, and infrastructure follows behavior.

That is what makes this moment so significant. The grain train to Mexico is not a temporary workaround; it is evidence of a reconfigured system. Canada is no longer merely hedging against U.S. unpredictability—it is building an alternative.

From Washington’s perspective, the change may appear incremental. No borders were closed. No treaties were torn up. But power in trade often shifts quietly, through decisions that accumulate until old assumptions collapse.

As trains continue to roll south carrying Canadian grain that no longer stops on American soil, the United States is being forced into an unfamiliar position: watching value move through its territory without capturing it.

In the end, the lesson is not just about agriculture. It is about adaptability. In a global economy defined by resilience and redundancy, those who control their routes control their future. Canada appears to have learned that lesson early—and acted on it decisively.