The Saint and the Seed

La Crosse, Wisconsin, 1878.

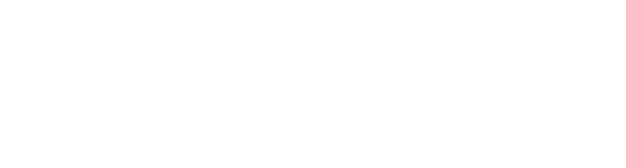

A child was born on a humid July night in a house that smelled of candle wax and sour milk. They named her Augusta Wilhelmine Gein, the daughter of poor German immigrants who measured sin more carefully than kindness. No one remembered her laughing. Even as a girl, she looked like someone carrying an invisible grievance against the world.

When Augusta grew up, she found God—then built a cage around Him. The Bible became less a book than a weapon. She read it as proof that pleasure was filth, that women were fallen, and that fear was the only road to salvation.

In 1900 she married George Philip Gein, a timid, alcoholic carpenter who trembled when she raised her voice. Neighbors said she never touched him unless she had to. Two sons followed: Henry George in 1901 and Edward Theodore in 1906. Augusta wanted a daughter; when another boy arrived, she called it God’s test.

From the beginning she ruled her household like a priestess. Her word was divine law. Her husband, dull and useless, disappeared into the bottle; her sons became acolytes. She saw the outside world as a sewer of temptation. To save her family, she would cut them off from it completely.

Around 1915 she moved them to a remote farm on the edge of Plainfield, Wisconsin—a flat, wind-scoured patch of nothing surrounded by marsh and silence. To her, isolation was purity. To everyone else, it was exile.

Scriptures of Poison

Every night after supper, Augusta lit a kerosene lamp and read from Revelation, Leviticus, Proverbs—the angriest chapters. Her sermons were steady, venomous.

“The world is filth. Women are the root of man’s corruption. Lust is the devil’s breath.”

The boys listened because there was nothing else to listen to. Outside, the wind howled across the fields; inside, her voice filled every corner of the dark wooden house.

For Edward—quiet, thin, inward—those words became law. He was taught to fear women, to despise desire, and to believe that his mother alone stood between him and damnation. Augusta’s religion was not faith but domination. She turned obedience into worship, and her son’s love into submission.

The Child Who Wasn’t Allowed to Live

Plainfield’s few children sometimes passed the Gein farm on their way to school. They waved. The younger boy never waved back. Augusta forbade it. “You will not speak to the damned,” she said.

When he once looked too long at a girl in town—a harmless glance at a smile—his mother made him kneel beside the stove until his knees blistered. Then she recited a psalm about impurity. He wept, not from pain but from shame.

Children are sponges. They absorb what the air gives them. Edward absorbed his mother’s fear until it became the shape of his own mind.

No Mirrors in the House

There were almost no mirrors inside the farmhouse. Augusta said they encouraged vanity. Instead, she kept crucifixes on every wall. The boy learned to see himself only through her eyes—never as a person, only as a reflection of sin or obedience.

Psychologists later called this identity diffusion. But there was nothing clinical about the way it felt. He existed only through her approval. When she praised him, the world made sense; when she scolded him, it shattered.

Henry, the older brother, sometimes rebelled—mocking their mother’s endless sermons, muttering that she was crazy. Augusta called him “ungrateful.” Edward called him “dangerous.”

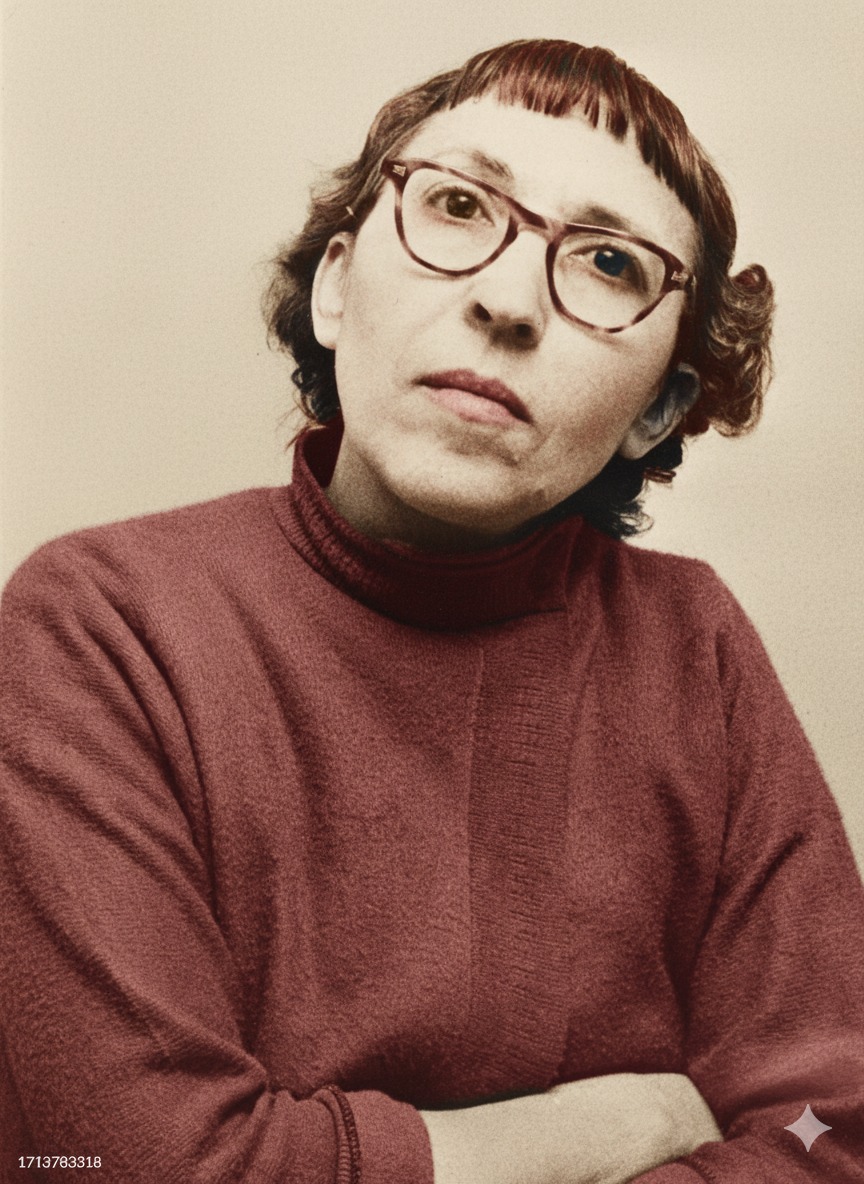

The House Tightens

The years folded in on themselves. Winters turned the farm into a white desert. Augusta’s voice grew harsher as her health failed. George Gein finally died in 1940—heart failure, exhaustion, or mercy, depending on who told it. At the funeral Augusta didn’t cry. She simply murmured, “The weak shall perish.”

Her younger son stood beside her, stiff as wood, waiting for permission to grieve. None came.

Something cracked inside him then—a silent fracture that never healed. He began speaking less, moving slower, staring longer at his mother’s face as if afraid it might vanish.

In 1944 a brush fire broke out near the property. The brothers tried to control it; when it was over, Henry was dead. Official cause: asphyxiation. Unofficial whispers: envy.

Neighbors recalled how Henry had criticized Augusta only days before, calling her “not a woman of God but a tyrant.”

Whether the younger brother killed him will never be proven. But when sheriff’s deputies told Augusta her eldest was gone, she simply nodded and said, “God has spoken.”

From that moment onward, the farmhouse belonged to two souls locked inside the same fever: one fading, one festering.