California Republicans entered the race with defiance in their eyes and a strategy they swore would outsmart Gavin Newsom’s political map. For weeks, they spoke of momentum, of a red surge ready to rewrite the state’s story.

Donors were courted, plans were drafted, and internal chatter painted Proposition 50 as the line in the sand that would finally stop Sacramento’s power play. But as the campaign wore on and the votes began to roll in, optimism slowly curdled into disbelief — and eventually into a heavy, echoing silence that said more than any press release ever could.

When the final numbers landed, the loss was devastating, and what unfolded behind closed doors laid bare just how fractured and unprepared their effort had been from the start.

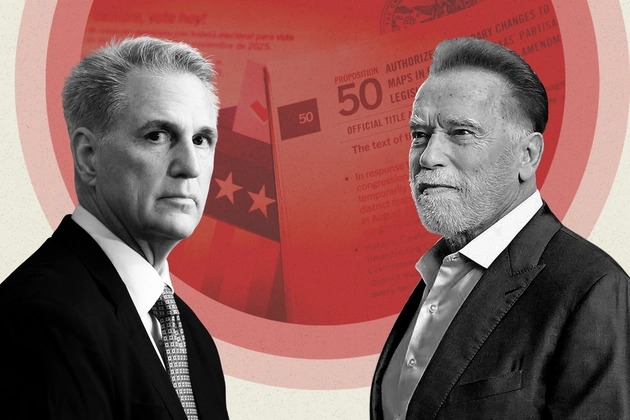

The story began with swagger. Charles Munger Jr., the physicist-turned-reform champion who had once poured millions into creating California’s independent redistricting commission, stepped back into the arena convinced he could save it. He committed tens of millions to a new committee, Protect Voters First, and surrounded himself with consultants who had helped him win fights in 2008 and 2010. Kevin McCarthy, fresh from the bruises of national leadership battles but still a towering figure in California GOP circles, privately floated eye-popping fundraising targets. Up to $100 million, he suggested, could be raised to stop Newsom’s mid-decade gerrymander in its tracks. On paper, it looked like the makings of a formidable counteroffensive.

There was also star power waiting in the wings. Arnold Schwarzenegger, the Republican ex-governor who had once been the face of good-government reform and the independent commission itself, signaled he was willing to speak out. Early on, he posted a photo of himself in the gym wearing a “terminate gerrymandering” shirt, a nostalgic callback to the days when Republicans and reformers claimed the moral high ground on fair maps. Good-government groups like California Common Cause and the League of Women Voters initially sounded open to reviving their old alliance with Munger, hinting at a broad coalition that could appeal to moderates and Democrats uneasy with tearing up the commission.

But the seams began to split almost as soon as the campaign took shape. Common Cause, after internal deliberations, publicly announced that Newsom’s plan met its “fairness criteria,” stunning allies who had assumed the group would stand with the commission’s original architects. The League of Women Voters declined to join the opposition at all, choosing neutrality. Schwarzenegger, after his early flourish, grew cautious. When Munger flew down to meet him, the former governor made it clear he would criticize the measure in his own way and on his own schedule, not as the official face of any “No” campaign. The grand, bipartisan reform front that Republicans expected simply never materialized.

Inside Munger’s camp, strategy and messaging became points of friction. Democrats quickly decided that if they couldn’t be seen as attacking “independent maps,” they could attack Munger himself: a wealthy Republican donor painted as out of touch and aligned with the national party’s ugliest caricatures. His advisers urged him to respond more assertively, to clarify his positions on social issues and to lean harder into a both-sides critique that condemned gerrymandering in Texas and California alike. There were proposals to hire demographers to show voters exactly how their communities would be sliced and reassembled under Prop 50. Instead, the campaign’s first big ad featured a kettlebell smashing wooden blocks labeled “Fair Elections” — a spot that looked more like a civics-class video than a hard-hitting statewide message. It aired heavily, even as some on the inside watched it and wondered if they’d just seen the campaign’s momentum die in real time.

McCarthy’s parallel effort, Stop Sacramento’s Power Grab, didn’t fare much better. Its mission was clear enough: fire up Republican voters and turn Prop 50 into a symbol of one-party rule gone too far. But the money to do that simply never showed up at the scale they’d promised. National donors, focused on redistricting fights in friendlier states and wary of California’s deep-blue tilt, saw the race as a luxury, not a necessity. Trump, whose influence could have jolted conservative fundraising circles, never made the contest a personal priority. Without that signal, big checks stayed on the sidelines.

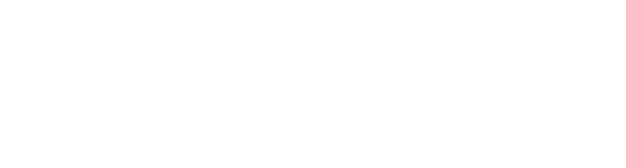

As Democrats flooded the airwaves and social media feeds with confident, polished messaging, the No side looked scattered and underpowered. Newsom leaned into his role as partisan warrior, framing Prop 50 as payback for Republican gerrymanders elsewhere and a necessary step to protect democracy from being gamed by the other side. His campaign experimented online, brought in influencers, and used every tool available to define the narrative. Meanwhile, the opposition struggled to even build a sizable following on basic platforms. Their digital presence was anemic — a few posts, a handful of followers — in a fight where online narrative was half the battlefield.

By late October, internal numbers told a grim story. Polls that once showed skepticism about rewriting maps had shifted decisively. The opposition’s cash burn had forced them to pull back on ads just as ballots were landing in mailboxes. Emergency money finally arrived from national Republican groups, but it was too little and too late. Mailers meant to rally conservative voters landed after many had already voted. Television buys looked tiny next to the governor’s juggernaut. What began as a confident stand for fairness had turned into a scramble just to stay visible.

When Election Day ended and the results became undeniable, the reckoning began. Prop 50 hadn’t just passed — it had passed decisively, delivering Newsom and Democrats exactly the kind of map Republicans had warned about. In private conversations, fingers pointed in every direction: at McCarthy for overpromising on money, at national leaders for writing off California, at consultants for weak ads, at good-government groups for abandoning their old cause, even at one another for failing to settle on a unified message before it was too late.

Yet beneath all the blame, a quieter truth settled in: their coalition had never truly been built on shared trust or clear strategy. It was a loose alliance held together by fear of Newsom’s power, not by a coherent plan to persuade a skeptical electorate. When stress hit, it fractured along old ideological lines — Trump versus anti-Trump, reformer versus partisan, national versus local priorities.

In the end, California Republicans didn’t just lose a ballot measure. They watched the very system they once championed as a model for the nation get brushed aside, while their response collapsed under the weight of its own dysfunction. The redistricting war will go on, in courts and future elections, but the battle over Prop 50 left a lasting imprint: a stark reminder that outrage and rhetoric aren’t enough. Without discipline, unity, and a message that speaks beyond their shrinking base, defiance at the starting line can still end in silence at the finish.